Saxons

Sahson | |

|---|---|

The Stem Duchy of Saxony | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Old Saxony, Frisia, England, Normandy | |

| Languages | |

| Old Saxon, Old English | |

| Religion | |

| Originally Germanic and Anglo-Saxon paganism, later Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Anglo-Saxons, Angles, Frisii, Jutes, Franks |

The Saxons were the Germanic people after whom Saxony (Latin: Saxonia) came to be named by the 8th century, near the North Sea coast of what is now northern Germany.[1] Before any clear historical mention of Saxony as a country, "Saxons" became important during the late Roman Empire, when the name was used to refer to a group of coastal pirates or raiders who attacked from the north, in a similar sense to the much later term Viking.[2] These early raiders and settlers were believed by contemporaries to come from coastal regions north of the Rhine and the homeland of the Franks. Significant numbers of them settled in what later became northern France and southern England.

There is possibly a single classical reference to a smaller and much earlier Saxon tribe, but the interpretation of this text ("Axones" in most surviving manuscripts) is disputed. According to this proposal, the original Saxon tribe lived north of the mouth of the Elbe, close to the probable homeland of the Angles.[3] The political history of the continental Saxons is unclear until the 8th century and the conflict between their semi-legendary hero Widukind and the Frankish emperor Charlemagne. Charles Martel, the grandfather of Charlemagne, fought and led numerous campaigns against the Saxons. Charlemagne defeated the Saxons after winning the long Saxon Wars (772-804), and forcing them to convert to Christianity, annexing Saxony into the Carolingian domain. Under the Carolingian Franks, Saxony became one of the original Stem Duchies which formed the basic political structure of the Holy Roman Empire. The early rulers of this early Duchy of Saxony expanded their territories to the east, at the expense of Slavic-speaking Wends.

Today the Saxons of Germany no longer form a distinctive ethnic group or country, but their name lives on in the names of several regions and states of Germany, including Lower Saxony (German: Niedersachsen) which includes most of the original duchy. Their language evolved into Low German which was until recently very widely spoken not only within Germany but also in the cities of the Hanseatic League. However, this has now largely been replaced by standard "High German", Dutch, and the languages of the areas surrounding the old trading cities.

In contrast, the Saxons settlers in England became part of a new Old English-speaking nation, now commonly referred to as the Anglo Saxons. This brought together local Romano-British populations, Saxons, and other migrants from the same North Sea region, including Frisians, Jutes, and Angles. The Angles are the source of the term English which became the more commonly-used collective term. The term Anglo-Saxon, combining the names of the Angles and the Saxons, came into use by the eighth century (for example in the work of Paul the Deacon) to distinguish the Germanic inhabitants of Britain from continental Saxons, but both the Saxons of Britain and those of Old Saxony in northern Germany continued to be referred to as "Saxons" in an indiscriminate manner.

Etymology

The name of the Saxons has traditionally been said to derive from a kind of knife used in this period and called a seax in Old English, Sax in German, sachs in Old High German, and sax in Old Norse.[4][5]

During the first centuries of its use the term Saxon was associated with raiders and not associated with any clearly defined homeland, apart from the settlements of Saxons in what are now England and Normandy. It is only much later that the medieval records of the Frankish empire began to refer to a largely inland nation of Saxons in what is now northern Germany. Although it became convenient to refer to the English Saxons as either English or as Anglo-Saxons after this point, the term Saxon was still used to refer to them for some time, and can be a source of potential confusion when interpreting contemporary records.

Possible mention in Ptolemy (2nd century AD)

Ptolemy's Geographia, written in the second century, is sometimes considered to contain the first mention of the Saxons. Some copies of this text mention a tribe called Saxones in the area to the north of the lower Elbe.[6] However, other versions refer to the same tribe as Axones. This may be a misspelling of the tribe that Tacitus in his Germania called Aviones. According to this theory, Saxones was the result of later scribes trying to correct a name that meant nothing to them.[7] On the other hand, Schütte, in his analysis of such problems in Ptolemy's Maps of Northern Europe, believed that Saxones is correct. He notes that the loss of first letters occurs in numerous places in various copies of Ptolemy's work, and also that the manuscripts without Saxones are generally inferior overall.[8]

Late Roman period (3rd-6th century AD)

The first undisputed mentions of the Saxon name come from the late 4th century, around the time of emperor Julian. By about 400 the Notitia Dignitatum shows that the Romans had created several military commands specifically to defend against Saxon raiders. The Litus Saxonicum ('Saxon Shore'), was composed of nine forts stretching around the south-eastern corner of England. On the other side of the English channel two coastal military commands were created, over the Tractus Armoricanus in what is now Brittany and Normandy, and the coast of Belgica Secunda in what later became Flanders and Picardy. The Notitia Dignitatum also lists the existence of a Saxon military unit (an Ala) in the Roman military, which was stationed in what is now Lebanon and northern Israel.[9] Several other records can be dated:

- Eutropius the historian, a contemporary and companion of Julian, claimed that Saxon and Frankish raiders had already attacked the North Sea coast near Boulogne-sur-Mer almost a century earlier in about 285, when Carausius was posted there to defend against them. Because the terms Saxon and Frank were well-known as the raiders of his time it is not certain whether the 3rd century raiders were also referred to this way.[10] Contemporary records mention only Franks in this period.

- Julian himself mentioned the Saxons in a speech as close allies of Magnentius in 350 when he declared himself emperor in Gaul. Julian described the Saxons and Franks as kinsmen of Magnentius himself, living "beyond the Rhine and on the shores of the western sea".[11]

- In 357/8 Julian clearly had contact with the Saxons himself when he campaigned in the Rhine region against Alemanni, Franks and Saxons. Franks and Saxons entered the Maas river area in what is now the Netherlands, and displaced the recently settled Salian Franks from Batavia, whereupon some of the Salians began to move south into the region of Texandria. This Frankish settlement within the empire eventually gained the acceptance from Julian, but according to the near contemporary Ammianus Marcellinus the Chamavi who had also entered the area were ejected.[12] Writing about this period more than a century later, it was Zosimus who mentioned the involvement of the Saxons and even mentioned a specific tribe, called the Kouadoi, which has been interpreted as a misunderstanding for the Chauci who had lived in this general region centuries earlier, or the Chamavi, mentioned by Amminanus, who were however sometimes considered to be Franks.

- In 368, during the reign of Valentinian I, Ammianus (books 26 and 27) reported that Britain was troubled by the Scoti, two tribes of Picts (the Dicalydones and Verturiones), the Attacotti and the Saxons. Count Theodosius, the father of the future emperor Theodosius I led a successful campaign to recover control in Britain.

- In Gaul in 370 (Ammianus, books 28 and 30) the Saxons "overcoming the dangers of the Ocean advanced at rapid pace towards the Roman frontier" invading the maritime districts in Gaul. Valentinian's forces tricked and overwhelmed them "and stripped of their booty the robbers thus forcibly crushed had almost returned enriched with the spoils which they took", by a "device which was treacherous but expedient".

- According to the Chronica Gallica of 452, which was probably written in southern France, Britain was ravaged by Saxon invaders in 409 or 410.

In these cases the Saxons were consistently associated with using boats for their raids, even upon the Maas delta region.

In 441–442 AD, Saxons are mentioned in the Chronica Gallica of 452 which says that the "British provinces, which to this time had suffered various defeats and misfortunes, are reduced to Saxon rule".[13][14] Some generations later Gildas seems to have described the same events, without dating them, as a revolt by a Saxon force based on the Isle of Thanet who were invited as foederati to Britain, in order to help defend against raids by Picts and Scots. By the time of Gildas in the 6th century the Romano-British had recovered control of the country but were now divided into corrupt "tyrannies". The subsequent centuries are not well recorded but the population of Old-English speakers increased and many of the small kingdoms of Britain eventually identified as English.[15]

In the 460s, an apparent fragment of a chronicle preserved in the History of the Franks of Gregory of Tours, gives a confusing report about a number of battles involving one "Adovacrius" who led a group of Saxons based upon islands somewhere near the mouth of the Loire. He took hostages at Anger in France, but his force was subsequently retaken by Roman and Frankish forces led by Childeric I. A "great war was waged between the Saxons and the Romans but the Saxons, turning their backs, with the Romans pursuing, lost many of their men to the sword. Their islands were captured and ravaged by the Franks, many people being killed." Though there is no consensus, many historians beleive that this Adovacrius may be the same person as the future king of Italy, who is mentioned in the same part of Gregory's text as a person who subsequently allied with Childeric to fight Alemanni in Italy.[16][17][18]

There was a Saxon population on the Normandy coast, near Bayeux. In 589, the Saxons from the Bessin region near Bayeux wore their hair in the Breton fashion at the orders of Fredegund and fought with them as allies against Guntram.[19] Beginning in 626, the Saxons of the Bessin were used by Dagobert I for his campaigns against the Basques. One of their own, Aeghyna, was created a dux over the region of Vasconia.[20] In 843 and 846 under king Charles the Bald, other official documents mention a pagus called Otlinga Saxonia in the Bessin region, but the meaning of Otlinga is unclear.

In 569, some Saxons from France accompanied the Lombards into Italy under the leadership of Alboin and settled there. In 572, they raided southeastern Gaul as far as Stablo, now Estoublon and easily defeated by the Gallo-Roman general Mummolus. They were allowed to return to Italy, gather their families and belongings and return to pass through the region again to return to the north. After plundering the countryside, they stopped from crossing the Rhône by Mummolus and forced to pay compensation for what they had robbed.[21]

Later Saxons in Germany

The use of the term "Saxons" to refer to inland inhabitants of present-day Northern Germany are first mentioned in 555, when the Frankish king Theudebald died, and the Saxons used the opportunity for an uprising. The uprising was suppressed by Chlothar I, Theudebald's successor. Some of their Frankish successors fought against the Saxons, others were allied with them. The Thuringians frequently appeared as allies of the Saxons.[citation needed]

The continental Saxons living in what was known as Old Saxony (c. 531–804) appear to have become consolidated by the end of the eighth century. After subjugation by the Emperor Charlemagne, a political entity called the Duchy of Saxony (804–1296) appeared, covering Westphalia, Eastphalia, Angria and Nordalbingia (Holstein, southern part of modern-day Schleswig-Holstein state).

The Saxons long resisted becoming Christians[22] and being incorporated into the orbit of the Frankish kingdom.[23] In 776 the Saxons promised to convert to Christianity and vow loyalty to the king, but, during Charlemagne's campaign in Hispania (778), the Saxons advanced to Deutz on the Rhine and plundered along the river. This was an oft-repeated pattern when Charlemagne was distracted by other matters.[23] They were conquered by Charlemagne in a long series of annual campaigns, the Saxon Wars (772–804). With defeat came enforced baptism and conversion as well as the union of the Saxons with the rest of the Germanic, Frankish empire. Their sacred tree or pillar, a symbol of Irminsul, was destroyed. Charlemagne deported 10,000 Nordalbingian Saxons to Neustria and gave their largely vacant lands in Wagria (approximately modern Plön and Ostholstein districts) to the loyal king of the Abotrites. Einhard, Charlemagne's biographer, says on the closing of this grand conflict:

The war that had lasted so many years was at length ended by their acceding to the terms offered by the king; which were renunciation of their national religious customs and the worship of devils, acceptance of the sacraments of the Christian faith and religion, and union with the Franks to form one people.

Under Carolingian rule, the Saxons were reduced to tributary status. There is evidence that the Saxons, as well as Slavic tributaries such as the Abodrites and the Wends, often provided troops to their Carolingian overlords. The dukes of Saxony became kings (Henry I, the Fowler, 919) and later the first emperors (Henry's son, Otto I, the Great) of Germany during the tenth century, but they lost this position in 1024. The duchy was divided in 1180 when Duke Henry the Lion refused to follow his cousin, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, into war in Lombardy.

During the High Middle Ages, under the Salian emperors and, later, under the Teutonic Knights, German settlers moved east of the Saale into the area of a western Slavic tribe, the Sorbs. The Sorbs were gradually Germanised. This region subsequently acquired the name Saxony through political circumstances, though it was initially called the March of Meissen. The rulers of Meissen acquired control of the Duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg (only a remnant of the previous Duchy) in 1423; they eventually applied the name Saxony to the whole of their kingdom. Since then, this part of eastern Germany has been referred to as Saxony (German: Sachsen), a source of some misunderstanding about the original homeland of the Saxons, with a central part in the present-day German state of Lower Saxony (German: Niedersachsen).

Language

Old English, associated with the Saxons in England, was closer to later recorded dialects of Old Frisian than the Old Saxon language. Old Frisian apparently once stretched along the North Sea coast from the northern Netherlands to southern Denmark, while Old Saxon originally didn't extend to the coast. Linguists have noted that Old Frisian and Old Saxon, although neighbouring and related, did not form part of the same dialect continuum. In contrast, the Saxon dialects became part of the much larger Continental West Germanic continuum which stretched to the Alps, and can all be considered to be types of German.

According to the historical linguist Elmar Seebold, this development can only be explained if continental Saxon society prior to the migration to Britain was effectively composed of two related, but different forms of West Germanic. In his view, the group of people who, in the 3rd century, first migrated southwards to what is now the northwestern portion of Lower Saxony spoke North Sea Germanic dialects closely related to Old Frisian and Old English. There, these migrants encountered an already present population whose language was significantly different from their own, i.e. belonging to the Weser–Rhine Germanic grouping, over whom they then formed an elite, lending their name to the subsequent tribal federation and region as a whole. Later, during the 5th century, as the Angles started migrating to Britain, the descendants of this elite joined them, while the descendants of the native inhabitants did not, or at least not significantly. As the languages of the Angles and this particular Saxon group were closely related, a continuum between Anglian and Saxon could form in Britain, which later became English. In the land of the Saxons itself, the departure of a large part of this former elite caused the sociopolitical landscape to change, and the original population, after the departure of the majority of the elite's descendants, became so predominant that their dialects (presumably the language of the Chauci, the language of the Thuringians, and possibly other ancient tribes) prevailed and ultimately formed the basis for the Low Saxon dialects known today, while their speakers retained the tribal name.[24]

-

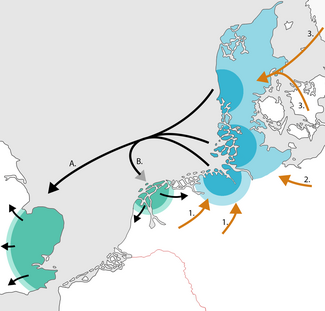

Position of North Sea Germanic dialects prior to the migration period (3rd century CE).Migration of the Saxons from the territory of the Angles (A.).Migration of Weser Rhine Germanic speakers towards the Roman limes (1.), southward migration of Elbe Germanic speakers (2.).

Position of North Sea Germanic dialects prior to the migration period (3rd century CE).Migration of the Saxons from the territory of the Angles (A.).Migration of Weser Rhine Germanic speakers towards the Roman limes (1.), southward migration of Elbe Germanic speakers (2.). -

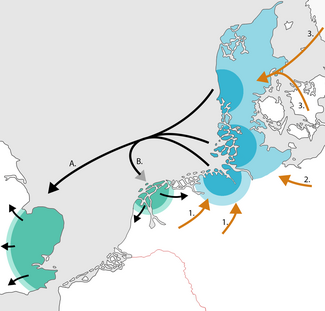

Position of North Sea Germanic dialects during the 5th and 6th century.Migration of North Germanic speakers (including the Saxon elite) to England (A.) and Frisia (B.)Migration of Weser Rhine Germanic speakers (1.), migration of West Slavic speakers (2.), migration of North Germanic speakers (2.).

Position of North Sea Germanic dialects during the 5th and 6th century.Migration of North Germanic speakers (including the Saxon elite) to England (A.) and Frisia (B.)Migration of Weser Rhine Germanic speakers (1.), migration of West Slavic speakers (2.), migration of North Germanic speakers (2.). -

Position of North Sea Germanic dialects (Old English & Old Frisian) directly following the migration period.10th/11th century migration of (Ems) Frisian speakers to the North German mainland (A.)

Position of North Sea Germanic dialects (Old English & Old Frisian) directly following the migration period.10th/11th century migration of (Ems) Frisian speakers to the North German mainland (A.)

Culture

Social structure

Bede, a Northumbrian writing around the year 730, remarks that "the old (that is, the continental) Saxons have no king, but they are governed by several ealdormen (or satrapa) who, during war, cast lots for leadership but who, in time of peace, are equal in power." The regnum Saxonum was divided into three provinces – Westphalia, Eastphalia and Angria – which comprised about one hundred pagi or Gaue. Each Gau had its own satrap with enough military power to level whole villages that opposed him.[25]

In the mid-9th century, Nithard first described the social structure of the Saxons beneath their leaders. The caste structure was rigid; in the Saxon language the three castes, excluding slaves, were called the edhilingui (related to the term aetheling), frilingi and lazzi. These terms were subsequently Latinised as nobiles or nobiliores; ingenui, ingenuiles or liberi; and liberti, liti or serviles.[26] According to very early traditions that are presumed to contain a good deal of historical truth, the edhilingui were the descendants of the Saxons who led the tribe out of Holstein and during the migrations of the sixth century.[26] They were a conquering warrior elite. The frilingi represented the descendants of the amicii, auxiliarii and manumissi of that caste. The lazzi represented the descendants of the original inhabitants of the conquered territories, who were forced to make oaths of submission and pay tribute to the edhilingui.

The Lex Saxonum regulated the Saxons' different society. Intermarriage between the castes was forbidden by the Lex Saxonum, and wergilds were set based upon caste membership. The edhilingui were worth 1,440 solidi, or about 700 head of cattle, the highest wergild on the continent; the price of a bride was also very high. This was six times as much as that of the frilingi and eight times as much as the lazzi. The gulf between noble and ignoble was very large, but the difference between a freeman and an indentured labourer was small.[27]

According to the Vita Lebuini antiqua, an important source for early Saxon history, the Saxons held an annual council at Marklo (Westphalia) where they "confirmed their laws, gave judgment on outstanding cases, and determined by common counsel whether they would go to war or be in peace that year."[25] All three castes participated in the general council; twelve representatives from each caste were sent from each Gau. In 782, Charlemagne abolished the system of Gaue and replaced it with the Grafschaftsverfassung, the system of counties typical of Francia.[28] By prohibiting the Marklo councils, Charlemagne pushed the frilingi and lazzi out of political power. The old Saxon system of Abgabengrundherrschaft, lordship based on dues and taxes, was replaced by a form of feudalism based on service and labour, personal relationships and oaths.[29]

Religion

Germanic religion

Saxon religious practices were closely related to their political practices. The annual councils of the entire tribe began with invocations of the gods. The procedure by which dukes were elected in wartime, by drawing lots, is presumed to have had religious significance, i.e. in giving trust to divine providence – it seems – to guide the random decision-making.[30] There were also sacred rituals and objects, such as the pillars called Irminsul; these were believed to connect heaven and earth, as with other examples of trees or ladders to heaven in numerous religions. Charlemagne had one such pillar chopped down in 772 close to the Eresburg stronghold.

Early Saxon religious practices in Britain can be gleaned from place names and the Germanic calendar in use at that time. The Germanic gods Woden, Frigg, Tiw and Thunor, who are attested to in every Germanic tradition, were worshipped in Wessex, Sussex and Essex. They are the only ones directly attested to, though the names of the third and fourth months (March and April) of the Old English calendar bear the names Hrēþmōnaþ and Ēosturmōnaþ, meaning 'month of Hretha' and 'month of Ēostre'. It is presumed that these are the names of two goddesses who were worshipped around that season.[31] The Saxons offered cakes to their gods in February (Solmōnaþ). There was a religious festival associated with the harvest, Halegmōnaþ ('holy month' or 'month of offerings', September).[32][page needed] The Saxon calendar began on 25 December, and the months of December and January were called Yule (or Giuli). They contained a Modra niht or 'night of the mothers', another religious festival of unknown content.

The Saxon freemen and servile class remained faithful to their original beliefs long after their nominal conversion to Christianity. Nursing a hatred of the upper class, which, with Frankish assistance, had marginalised them from political power, the lower classes (the plebeium vulgus or cives) were a problem for Christian authorities as late as 836. The Translatio S. Liborii remarks on their obstinacy in pagan ritus et superstitio ('usage and superstition').[33]

Christianity

The conversion of the Saxons in England from their original Germanic religion to Christianity occurred in the early to late seventh century under the influence of the already converted Jutes of Kent. In the 630s, Birinus became the "apostle to the West Saxons" and converted Wessex, whose first Christian king was Cynegils. The West Saxons begin to emerge from obscurity only with their conversion to Christianity and keeping written records. The Gewisse, a West Saxon people, were especially resistant to Christianity; Birinus exercised more efforts against them and ultimately succeeded in conversion.[31] In Wessex, a bishopric was founded at Dorchester. The South Saxons were first evangelised extensively under Anglian influence; Aethelwalh of Sussex was converted by Wulfhere, King of Mercia and allowed Wilfrid, Bishop of York, to evangelise his people beginning in 681. The chief South Saxon bishopric was that of Selsey. The East Saxons were more pagan than the southern or western Saxons; their territory had a superabundance of pagan sites.[34] Their king, Saeberht, was converted early and a diocese was established at London. Its first bishop, Mellitus, was expelled by Saeberht's heirs. The conversion of the East Saxons was completed under Cedd in the 650s and 660s.

The continental Saxons were evangelised largely by English missionaries in the late seventh and early eighth centuries. Around 695, two early English missionaries, Hewald the White and Hewald the Black, were martyred by the vicani, that is, villagers.[30] Throughout the century that followed, villagers and other peasants proved to be the greatest opponents of Christianisation, while missionaries often received the support of the edhilingui and other noblemen. Saint Lebuin, an Englishman who between 745 and 770 preached to the Saxons, mainly in the eastern Netherlands, built a church and made many friends among the nobility. Some of them rallied to save him from an angry mob at the annual council at Marklo (near river Weser, Bremen). Social tensions arose between the Christianity-sympathetic noblemen and the pagan lower castes, who were staunchly faithful to their traditional religion.[35][page needed]

Under Charlemagne, the Saxon Wars had as their chief object the conversion and integration of the Saxons into the Frankish empire. Though much of the highest caste converted readily, forced baptisms and forced tithing made enemies of the lower orders. Even some contemporaries found the methods employed to win over the Saxons wanting, as this excerpt from a letter of Alcuin of York to his friend Meginfrid, written in 796, shows:

If the light yoke and sweet burden of Christ were to be preached to the most obstinate people of the Saxons with as much determination as the payment of tithes has been exacted, or as the force of the legal decree has been applied for fault of the most trifling sort imaginable, perhaps they would not be averse to their baptismal vows.[36]

Charlemagne's successor, Louis the Pious, reportedly treated the Saxons more as Alcuin would have wished, and as a consequence they were faithful subjects.[37] The lower classes, however, revolted against Frankish overlordship in favour of their old paganism as late as the 840s, when the Stellinga rose up against the Saxon leadership, who were allied with the Frankish emperor Lothair I. After the suppression of the Stellinga, in 851 Louis the German brought relics from Rome to Saxony to foster a devotion to the Roman Catholic Church.[38] The Poeta Saxo, in his verse Annales of Charlemagne's reign (written between 888 and 891), laid an emphasis on his conquest of Saxony. He celebrated the Frankish monarch as on par with the Roman emperors and as the bringer of Christian salvation to people. References are made to periodic outbreaks of pagan worship, especially of Freya, among the Saxon peasantry as late as the 12th century.

Christian literature

In the ninth century, the Saxon nobility became vigorous supporters of monasticism and formed a bulwark of Christianity against the existing Slavic paganism to the east and the Nordic paganism of the Vikings to the north. Much Christian literature was produced in the vernacular Old Saxon, the notable ones being a result of the literary output and wide influence of Saxon monasteries such as Fulda, Corvey and Verden; and the theological controversy between the Augustinian, Gottschalk and Rabanus Maurus.[39]

From an early date, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious supported Christian vernacular works in order to evangelise the Saxons more efficiently. The Heliand, a verse epic of the life of Christ in a Germanic setting, and Genesis, another epic retelling of the events of the first book of the Bible, were commissioned in the early ninth century by Louis to disseminate scriptural knowledge to the masses. A council of Tours in 813 and then a synod of Mainz in 848 both declared that homilies ought to be preached in the vernacular. The earliest preserved text in the Saxon language is a baptismal vow from the late eighth or early ninth century; the vernacular was used extensively in an effort to Christianise the lowest castes of Saxon society.[40]

Saxon as a demonym

Celtic languages

In the Celtic languages, the words designating English nationality derive from the Latin word Saxones. The most prominent example, a loanword in English from Scottish Gaelic (older spelling: Sasunnach), is the word Sassenach, used by Scots-, Scottish English- and Gaelic-speakers in the 21st century[41] as a racially pejorative term for an English person and, traditionally, to the English-speaking lowlanders of Scotland.[42] The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) gives 1771 as the date of the earliest written use of the word in English. The Gaelic name for England is Sasann (older spelling: Sasunn, genitive: Sasainn), and Sasannach (formed with a common adjective suffix -ach[43]) means 'English' in reference to people and things, though not when naming the English language, which is Béarla.

Sasanach, the Irish word for an Englishman (with Sasana meaning England), has the same derivation, as do the words used in Welsh to describe the English people (Saeson, singular Sais) and the language and things English in general: Saesneg and Seisnig.

Cornish terms the English Sawsnek, from the same derivation. In the 16th century Cornish-speakers used the phrase Meea navidna cowza sawzneck to feign ignorance of the English language.[44] The Cornish words for the English people and England are Sowsnek and Pow Sows ('Land [Pays] of Saxons'). Similarly Breton, spoken in north-western France, has saoz(on) ('English'), saozneg ('the English language'), and Bro-saoz for 'England'.

Romance languages

The label Saxons (in Romanian: Sași) also became attached to German settlers who settled during the 12th century in southeastern Transylvania.[45] From Transylvania, some of these Saxons migrated to neighbouring Moldavia, as the name of the town Sascut, in present-day Romania, shows.

Non-Indo-European languages

The Finns and Estonians have changed their usage of the root Saxon over the centuries to apply now to the whole country of Germany (Saksa and Saksamaa respectively) and the Germans (saksalaiset and sakslased, respectively). The Finnish word sakset (scissors) reflects the name of the old Saxon single-edged sword – seax – from which the name Saxon supposedly derives.[46] In Estonian, saks means colloquially, 'a wealthy person'. As a result of the Northern Crusades, Estonia's upper class comprised mostly Baltic Germans, persons of supposedly Saxon origin until well into the 20th century.

Saxony as a later toponym

Following the downfall of Henry the Lion (1129–1195, Duke of Saxony 1142–1180), and the subsequent splitting of the Saxon tribal duchy into several territories, the name of the Saxon duchy was transferred to the lands of the Ascanian family. This led to the differentiation between Lower Saxony (lands settled by the Saxon tribe) and Upper Saxony (the lands belonging to the House of Wettin). Gradually, the latter region became known as Saxony, ultimately usurping the name's original geographical meaning. The area formerly known as Upper Saxony now lies in Central Germany – in the eastern part of the present-day Federal Republic of Germany: note the names of the federal states of Saxony and Saxony-Anhalt.

Notes

- ^ Springer 2004, p. 12: "Unter dem alten Sachsen ist das Gebiet zu verstehen, das seit der Zeit Karls des Großen (reg. 768–814) bis zum Jahre 1180 also Saxonia '(das Land) Sachsen' bezeichnet wurde oder wenigstens so genannt werden konnte."

- ^ Springer 2004, p. 12: "Im Latein des späten Altertums konnte Saxones als Sammelbezeichnung von Küstenräubern gebraucht werden. Es spielte dieselbe Rolle wie viele Jahrhunderte später das Wort Wikinger."

- ^ Springer 2004, pp. 27–31.

- ^ "Saxon | Definition of Saxon in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 10 March 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "sax". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Saxony" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Green, D. H.; Siegmund, F. (2003). The Continental Saxons from the Migration Period to the Tenth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective. Boydell Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-84383-026-9.

- ^ Schütte 1917, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Springer 2004, p. 45.

- ^ Springer 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Springer 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Haywood, John (January 1991). Dark Age Naval Power: A Re-Assessment of Frankish and Anglo-Saxon Seafaring ... Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 9780415063746 – via Google Books.

- ^ Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ Springer 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Halsall, Guy (2013). Worlds of Arthur: Facts & Fictions of the Dark Ages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198700845.

- ^ Reynolds & Lopez 1946, p. 45. sfn error: no target: CITEREFReynoldsLopez1946 (help)

- ^ Gregory of Tours (1974). History of the Franks. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140442953.

- ^ (Springer 2004, p. 54) "In der Tat gewinnt seit zwanzig Jahren die Meinung an Boden, dass es sich um ein und deselbe Persönlichkeit gehandelt habe."

- ^ Bachrach 1971, p. 63.

- ^ Fredegar 1960, p. 66.

- ^ Bachrach 1971, p. 39.

- ^ "They are much given to devil worship," Einhard said, "and they are hostile to our religion," as when they martyred the Saints Ewald.

- ^ a b Lieberman, Benjamin (22 March 2013). Remaking Identities: God, Nation, and Race in World History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-4422-1395-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Seebold, Elmar (2003). "Die Herkunft der Franken, Friesen und Sachsen". Essays on the Early Franks. Barkhuis. pp. 24–29. ISBN 9789080739031.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Goldberg 1995, p. 473.

- ^ a b Goldberg 1995, p. 471.

- ^ Goldberg 1995, p. 472.

- ^ Goldberg 1995, p. 476.

- ^ Goldberg 1995, p. 479.

- ^ a b Goldberg 1995, p. 474.

- ^ a b Stenton 1971, p. 97–98.

- ^ Stenton 1971.

- ^ Goldberg 1995, p. 480.

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 102.

- ^ Goldberg 1995.

- ^ Goldberg 1995, p. 478.

- ^ Hummer 2005, p. 141, based on Astronomus.

- ^ Hummer 2005, p. 143.

- ^ Goldberg 1995, p. 477.

- ^ Hummer 2005, p. 138–139.

- ^ "Definition of SASSENACH". Merriam-Webster, Inc. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Scott, Walter (1871). The Lady of the Lake. T. Nelson and Sons.

- ^ "Sassenach". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Richard Carew, Survey of Cornwall, 1602. N.B. in revived Cornish, this would be transcribed, My ny vynnaf cows sowsnek. The Cornish word Emit meaning 'ant' (and perversely derived from Old English) is more commonly used in Cornwall as of 2015[update] as slang to designate non-Cornish Englishmen.

- ^ Magazin Istoric (5 September 2013). "Saşii – Saxonii Transilvaniei". Politeia (in Romanian).

- ^ Suomen sanojen alkuperä. Etymologinen sanakirja (in Finnish). Vol. 3. R-Ö. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura, Kotimaisten kielten tutkimuskeskus. 2012. p. 146.

References

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1971). Merovingian Military Organisation, 481–751. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Goldberg, Eric J. (July 1995). "Popular Revolt, Dynastic Politics, and Aristocratic Factionalism in the Early Middle Ages: The Saxon Stellinga Reconsidered". Speculum. 70 (3). University of Chicago Press: 467–501. doi:10.2307/2865267.

- Hummer, Hans J. (2005). Politics and Power in Early Medieval Europe: Alsace and the Frankish Realm 600–1000. Cambridge University Press.

- Reuter, Timothy (1991). Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman.

- "The Annals of Fulda: Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II". Medieval Sourcesonline. Manchester Medieval. Translated by Reuter, Timothy. Manchester University Press. 1992. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- Schütte, Gudmund (1917). Ptolemy's maps of northern Europe, a reconstruction of the prototypes. Copenhagen: H. Hagerup – via Archive.org.

- Springer, Matthias (2004). Die Sachsen (in German). Kohlhammer Verlag.

- Stenton, Sir Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its Continuations. Translated by Wallace-Hadrill, John Michael. Connecticut: Greenwood Press. 1960. Archived from the original on 3 February 2006.

- Thompson, James Westfall (1928). Feudal Germany. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co.

External links

- James Grout: Saxon Advent, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Saxons and Britons

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Saxons" . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- v

- t

- e

- Alemanni

- Adrabaecampi

- Angles

- Anglo-Saxons

- Ambrones

- Ampsivarii

- Angrivarii

- Armalausi

- Auiones

- Avarpi

- Baemi

- Baiuvarii

- Banochaemae

- Bastarnae

- Batavi

- Belgae

- Bateinoi

- Betasii

- Brondings

- Bructeri

- Burgundians

- Buri

- Cananefates

- Caritni

- Casuari

- Chaedini

- Chaemae

- Chamavi

- Chali

- Charudes

- Chasuarii

- Chattuarii

- Chatti

- Chauci

- Cherusci

- Cimbri

- Cobandi

- Corconti

- Cugerni

- Danes

- Dauciones

- Dulgubnii

- Favonae

- Firaesi

- Fosi

- Franks

- Frisiavones

- Frisii

- Gambrivii

- Geats

- Gepids

- Goths

- Gutes

- Harii

- Hermunduri

- Heruli

- Hilleviones

- Ingaevones

- Irminones

- Istvaeones

- Jutes

- Juthungi

- Lacringi

- Lemovii

- Lombards

- Lugii

- Marcomanni

- Marsacii

- Marsi

- Mattiaci

- Nemetes

- Njars

- Nuithones

- Osi

- Quadi

- Reudigni

- Rugii

- Rugini

- Saxons

- Semnones

- Sicambri

- Sciri

- Sitones

- Suarines

- Suebi

- Sunici

- Swedes

- Taifals

- Tencteri

- Teutons

- Thelir

- Thuringii

- Toxandri

- Treveri

- Triboci

- Tubantes

- Tulingi

- Tungri

- Ubii

- Usipetes

- Vagoth

- Vandals

- Vangiones

- Varisci

- Victohali

- Vidivarii

- Vinoviloth

- Warini

Category

Category